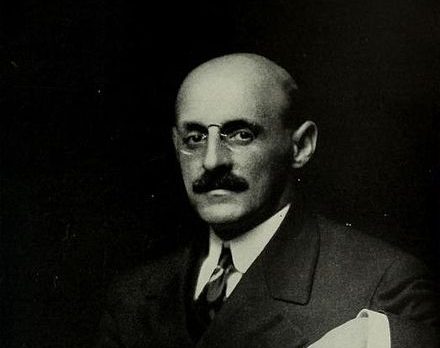

DEDICATING FULD HALL: Albert Einstein takes center stage for this photograph on May 22, 1939 at the dedication ceremony for the Institute for Advanced Study’s new building, Fuld Hall. From left: Alanson B. Houghton, C. Lavinia Bamberger (Louis Bamberger’s sister), Albert Einstein, Mrs. Abraham Flexner (the successful Broadway playwright Anne Crawford), Abraham Flexner, John R. Hardin, Herbert H. Maass, and President of Princeton University Harold W. Dodds. (Image Courtesy of Institute for Advanced Study, Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center)

Christine Di Bella, archivist at the Institute for Advanced Study, spoke to an audience of almost 100 at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory last week about the history of the Institute for Advanced Study.

The provocative title of Ms. Di Bella’s talk, “The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge: The History of the Institute for Advanced Study” was a big draw for technician John Adams, currently working on PPPL’s National Spherical Torus Experiment in magnetic fusion. “I am not a physicist and so I really appreciate talks that are geared toward a general audience. Most researchers here are working on very specific areas and this topic has a broad appeal.”

Ms. Di Bella opened her Powerpoint presentation with an image of the Institute’s Founding Director Abraham Flexner and explained that her talk’s title comes from an oft-given speech by Flexner, published in Harpers in 1939.

There is a playful quality to Flexner’s title. He was not altogether unconcerned with practical applications of scholarship, as is attested by his efforts to add faculty in economics and politics and in humanistic studies to the initial collection of mathematicians and theoretical scientists.

Flexner’s “useless” knowledge refers to intellectual and spiritual or humanistic pursuits. His defense is made in the context of an increasingly materialistic world. He is arguing for curiosity over pragmatism, for “useless” pursuits that give life significance. In effect, he wants a broader conception of what is regarded as “useful,” one that recognizes the “roaming and capricious possibilities of the human spirit.” His article is worth reading and can be viewed online courtesy of the Institute’s library (http://library.ias.edu/files/

In it, Flexner recounts a conversation he once had with Kodak founder George Eastman, in which they argued who should be named “the most useful worker in science in the world.” Eastman picks radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi. Flexner picks theoretical scientist James Clerk Maxwell (among others) whose curiosity about electricity and magnetism resulted in the formulae and theories that made Marconi’s work possible. According to Flexner, “curiosity, which may or may not eventuate in something useful, is probably the outstanding characteristic of modern thinking. It is not new. It goes back to Galileo, Bacon, and to Sir Isaac Newton, and it must be absolutely unhampered.”

Flexner cites advances in technology that have ultimately resulted from the work of other theoretical scientists as he pleads for the freedom to pursue unfettered curiosity. But, he points out, such ultimate, unforeseen and unpredictable practical results are not a justification for curiosity, but rather a sort of happy by-product.

Not everyone gets it. One who does, is philanthropist Warren Buffet who regards Flexner as his “hero.” When he attended the Forbes 400 Summit on Philanthropy last year at the main branch of the New York Public Library, Mr Buffett brought along a copy of Flexner’s 1940 autobiography,

“The Institute for Advanced Study,” said Ms. Di Bella, “is a place to take risks, where curiosity is valued, where scholars are under no obligation to do what they say they will do when they apply for admission but are free to pursue ‘unfettered research.’”

Some of the characteristics that make for “Advanced Study,” she explained, were put in place right from the start when Flexner determined there would be no classes, no grades, and no degrees. Although the Institute is authorized by the New Jersey Department of Education to bestow doctoral degrees it has never done so. It was to have a small permanent faculty and have Fellows, now called “Members,” come for temporary stays, typically one year at a time. “The Institute hasn’t changed that much,” she said.

“The idea was not that the permanent faculty would direct the work of these visitors, but rather the two would form a community of scholars learning from each other, with faculty available for counsel as needed,” said Ms Di Bella. “Work was to be mostly at the post-doctoral level, with newly minted PhDs rubbing shoulders with senior scholars on sabbaticals, and everything in between.”

After Flexner’s tenure as Institute director ended in 1939, he wrote four books in the next two decades. At the age 81, he enrolled in classes at Columbia University; a photograph in

Einstein and Veblen

Albert Einstein, of course, figures large in any history of the Institute, but Ms. Di Bella was careful to balance the influence of the most famous scientist in the world with other IAS figures such as Oswald Veblen, without whose initial involvement the Institute would be very different today. She also spoke briefly about the Electronic Computer Project and the Institute founders Louis Bamberger and Caroline Bamberger Fuld.

Ms. Di Bella joined the Institute’s Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center at the Institute in 2009 after archives positions with the Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries (PACSCL), the 92nd Street Y, the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan, and Harvard Business School. She holds an MS in Information from the University of Michigan’s School of Information and a bachelor’s degree in English from Wesleyan University.

One of the world’s leading centers for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry, the Institute was founded in 1930, and has been the intellectual home of diverse scholars including Erwin Panofsky, John von Neumann, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Freeman Dyson, Kurt Gödel, George Kennan, Clifford Geertz, Joan Wallach Scott, and Edward Witten. The Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center is located in the Institute’s Historical Studies-Social Science Library.

In the interests of full disclosure, it should be said that this reporter is a former employee of the Institute for Advanced Study, and currently works as an independent consultant there. She also authored a pictorial history of the Institute for the Arcadia Books Images of America series, published in 2011.

Written by: